September 2, 2025

By Grant Van Leuven

As I prepare to enter a one-year chaplaincy residency program next month with the San Diego VA Medical Center, it is useful to revisit some things I wrote as as a result of taking the “Intro to Chaplaincy” online class with my seminary (RPTS) about this time last year. First, this article that ran last November with Reformation21, “The Ministry of Presence.” But also, what follows below for one of my class research papers (largely making use of our wonderful church library).

Thomas Goodwin, a noteworthy Westminster Assembly divine, served as a chaplain to lord protector Oliver Cromwell during an incredible moment of England’s history of church and state. While details of this chaplaincy are sparse, meaningful moments can be discovered along the trajectory of Goodwin’s civil service under Cromwell that led to intimately caring for him at his death bed providing assurance in a context of a closely developed “ministry of presence” relationship.1

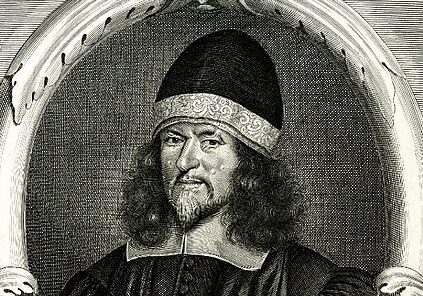

Thomas Goodwin:

The leader of the Independent and Congregational Puritans throughout his life, Thomas Goodwin (1600–1679) was a regularly invited and revered speaker to Parliament and the House of Commons; he also was asked by the House of Lords to oversee the papers that would be printed for the Westminster Assembly.2

In his “Memoir of Thomas Goodwin,” Robert Halley shares about the cultural influence within which Goodwin studied and taught for Cambridge: “At that time the Puritan cause had so many adherents both in the University and the town, that Cambridge was said to be a ‘nest of Puritans ;’ Goodwin says ‘the whole town was filled with the discourse of the power of Mr Perkins’ ministry.’”3 Perhaps William Perkins’ example outside of church preaching “ … zealously … to the neglected prisoners in the castle, many of whom ‘gladly received the word …” rubbed off on Goodwin’s later chaplaincy to Cromwell.4 Further, William Spurstow, who was Master at Catherine Hall where Goodwin served as a fellow—and who also was a commissioner of the Savoy conference which Goodwin later led, also was chaplain to Hampden’s regiment.5 So there were influencers whom Goodwin may have been motivated by and modeled in his chaplaincy to Cromwell.

Thomas Goodwin and Oliver Cromwell:

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) led parliamentary forces amid the civil wars in England for which he was lord protector along with Scotland and Ireland from 1653–58 during the republican Commonwealth.6 When he became head of England he promoted Independency as its official religion and asked Goodwin to serve as one of his chaplains and as a preacher at Oxford.7 Naturally, with the same commitment for the reformation of state and church and similar desire for an independent congregational model, Goodwin and Cromwell would be kindred spirits.

According to Halley, “On the 7th of June 1649, … Goodwin and Owen preached before Cromwell and the Parliament … and it was referred to the Oxford Committee to prefer [them] to be Heads of Colleges in that university … it was ordered … that Mr Thomas Goodwin be President of Magdalene College in Oxford … whom Cromwell appointed8 … Additionally, on September 4, Cromwell’s second Parliament assembled “with much formality and state” and “Goodwin, who had become a favourite of the Protector, preached on the occasion …The sermon is not extant, but we may infer its subject from the references made to it by Cromwell in the speech with which he introduced the proceedings of the House:—

‘ … you had to-day in the sermon … much recapitulation of providence, much allusion to a state and dispensation of discipline and correction, of mercies and deliverances—to a state and dispensation similar to ours—to, in truth, the only parallel of God’s dealing with us that I know in the world, which was largely and wisely held forth to you this day … and that having been so well remonstrated …

‘You were told to-day of a people brought out of Egypt, towards the land of Canaan … I do therefore persuade you to a sweet, gracious, and holy understanding of one another, and of your business, concerning which you had so good counsel this day, which, as it rejoiced my heart to hear, so I hope the Lord will imprint it upon your spirits.’” [Emphasis added.]9

Clearly, Cromwell was so pleased with his ministry to civil leaders that Goodwin felt inclined to leverage the Protector’s mutual affinity and affection for what would lead to the ecclesiastical Savoy Declaration:

During the prosperity of the Independent, under the protection of Cromwell, Goodwin and others thought it desirable to publish a declaration of their faith and discipline … On June 15, 1658, a preliminary meeting was convened by an invitation which seems … to have been of an official character, though, according to Neal, permission to hold the synod was reluctantly conceded by Cromwell.10

Though Cromwell was apparently hesitant about a potentially divisive effort, the fact that he conceded shows the fond relations he had with Goodwin, “a great favorite with Oliver Cromwell, who considered him an eminent instrument in propagating the gospel, and a great luminary in the church,”11 and who, “ … rose into high favour with the Protector, and was one of his intimate advisers …”12 No doubt, this came not only from public proclamation but personal presence.

Joel R. Beeke and Randall J. Pederson aver that, “During this decade [when Cromwell commissioned Owen and Goodwin to posts at Oxford], Goodwin was probably closer to Cromwell than any other Independent divine. He attended the Lord Protector on his deathbed.”13

Goodwin’s Chaplain Service to Cromwell Leading to Hospice Care:

Along with John Owen and others, Goodwin served as chaplain to Oliver Cromwell from 1656 until attending to him while the Lord Protector was dying.14

In her biography on Cromwell, Antonia Fraser tells of his wrestling with feverish doubts while nearing death: “There was a story that Oliver on one occasion turned anxiously to a minister and asked: ‘Tell me, is it possible to fall from Grace?’ The minister replied soothingly that no, it was not possible. At this the Protector relaxed once more and sighed: ‘I am safe, for I know that I was once in Grace.’”15 As do most others, Neal identifies that consoling minister as “Dr. Goodwin.”16

Portraying the sense of sadness among the whole and Goodwin in particular while dreading the need to likely be ready to appoint the next in line for leadership, Fraser shares the scene: “On Thursday, 2 September the Council at last galvanized itself to act concerning the succession, although the Independent ministers were still praying confidently in terms which presupposed the Protector’s recovery. Ludlow recorded the prayer of one such, Dr. Goodwin: ‘Lord, we ask not for his life, for that we are sure of: but that he may serve thee better than ever before.’”17 She notes how the medical doctors quipped that the chaplains were trying to “impose on God,’” and suspects “a curious attitude of certainty which persisted in a fashion even after Cromwell’s death: at the fast held by the Cromwellian household thereafter, Goodwin informed God that he had deceived them.”18 Halley gives a similar synopsis, but with important qualification:

Goodwin and others … were praying for [Cromwell’s] recovery, too confidently perhaps, for it must have been hard for them to think that he whom, as they thought, God had raised up to make England a truly Protestant country, was about to be removed while his great work was unfinished … In the excitement caused by their disappointment, Goodwin is reported to have said, in the words of Jeremiah, ‘O Lord, thou hast deceived me, and I was deceived,’ Jer. xx. 7. If he did say so, he undoubtedly appropriated the words of the prophet in their original signification, as expressive of very sore disappointment.19

Halley adds that after Cromwell died, Goodwin along with others, “ … attested upon oath, before the Privy Council, that Oliver in his last hours had nominated Richard as his successor, who was proclaimed accordingly, to the great joy of the Independents,” and Goodwin preached for the next Parliament of the new Protector at the Abbey before the Lords and House of Commons” on Psalm 85:10.20 So as a good chaplain, Goodwin not only cared for Cromwell in his life and on his deathbed, but then ministered to his family, colleagues, and country mourning his loss and preparing to move forward while honoring the lord protector’s memory and service to their nation. And just as he provided affirmation to Cromwell during his life, so at the end of his life Goodwin offered him assurance—for, as his epitaph written in Latin later on his own tombstone read, with a chaplain’s heart, “he was a pacifier of troubled consciences … a truly Christian pastor.”21

Grant Van Leuven has been feeding the flock at the Puritan Reformed Presbyterian Church in San Diego, CA, since 2010. A bi-vocational pastor, he also serves as Site Manager of the San Diego office for World Relief Southern California. Grant and his wife, Fernanda, have eight covenant children. He earned his M.Div. at the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Pittsburgh, PA.

Footnotes

- The phrase, “ministry of presence,” is frequently highlighted as the overarching governing concept of all chaplain ministry. This insight was gained from a recent class, “Intro to Chaplaincy,” at the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary taught by visiting professor Dr. Michael Stewart, Associate Endorser of Civilian Chaplains for the Presbyterian and Reformed Commission on Chaplains and Military Personnel (PRCC): see https://pcamna.org/staff/michael-stewart. ↩︎

- Joel R. Beeke and Randall J. Pederson, Meet the Puritans: With a Guide to Modern Reprints (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2006), 270. ↩︎

- Robert Halley, “Memoir of Thomas Goodwin, D.D.,” in The Works of Thomas Goodwin, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: James Nichol, 1861), xii. ↩︎

- Ibid, xiii. ↩︎

- Ibid, xix. ↩︎

- britannica.com/biography/Oliver-Cromwell. ↩︎

- thelogcollege.wordpress.com/2018/12/06/the-story-of-thomas-goodwin-too-short-to-take-communion. ↩︎

- Ibid, xxx, xxxiv. ↩︎

- Ibid, xxxvi. ↩︎

- Ibid, xxxvi-xxxvii. ↩︎

- apuritansmind.com/the-puritan-era/puritan-memoirs/puritan-memoirs-mr-thomas-goodwin. ↩︎

- digitalpuritan.net/thomas-goodwin. ↩︎

- Beeke and Pederson, 272. ↩︎

- digitalpuritan.net/thomas-goodwin. ↩︎

- Antonia Fraser, Cromwell: The Lord Protector (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973), 674. ↩︎

- Daniel Neal, The History of the Puritans, vol. 2 (Minneapolis: Klock & Klock Christian Publishers, 1979), 696. ↩︎

- Fraser, 675. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Halley, xxxvii. ↩︎

- Ibid, xxxviii. ↩︎

- Beeke and Penderson, 273. ↩︎